Why China

Everyone knows the fable of the white boy from the States who falls in love with Chinese culture and one day, when he's old enough, somehow makes himself the thousand-mile journey to the East. The fable has many protagonists: the skinny boy picking up Kung Fu, the jaded hippie who stumbles upon the Tao Te Ching, or the history geek enmeshed in the legends of warring kingdoms and dueling generals. No "Sinitic Bildungsroman" begins the same way, and in a country as big as China, the ending is fittingly unknowable. The boy may return to take over the family business, go join the Navy, or simply disappear into seas and mountains of the Chinese masses[1], never to be heard from again.

Yet from the vantage point of this white boy, a single thread ties these narratives of American encounters in China into a brilliant tapestry, and one not easily unwound by the ennui of neoliberal society, nor academic deconstruction of the "Orient," nor the most divisive strains of racial essentialism. That thread is uncertainty. It is the possibility of change, the possibility that the dogmatism of our peers is ungrounded. The possibility that life's meaning is not objective, not simply another ruler to measure up against, but a hidden, overgrown path only we can see. What the naysayers fail to understand is that the root of this uncertainty has little to do with what China is actually like. What matters more, is that the West has codified its neoliberal orthodoxy--the combination of a laissez faire legal system, decentralized governance, and electoral democracy--and that China increasingly asserts its right to an centralized, activist state managed hierarchically by the CCP. This refusal to cooperate with the West's "End to History" not only justifies an ongoing project reevaluation of politics, but also implicates the supposed objectivity of life's meaning. Rather than looking at China as a reflection of our own fears or future, I think we should treat it as a subject unto itself.

Let me unpack my reasoning. Citizens of the People's Republic of China with few excepts undergo an upbringing radically different from my own. The education system, which merits future discussion, is at the center of Chinese adolescence and highlights these differences: heavy focus on testing, a military-style timetable, dogmatic delivery of ethical and political thought. China under PRC rule has undergone dramatic changes, yet there is a strong path dependence. From about three thousand years ago when the earliest "surviving" Chinese classics were composed, we find identifiable antecedents of modern society, such as an emphasis on education and perceived equivalence between filial love and patriotism.

If that claim stinks of Orientalism, I'll admit that charge. Infantilization of foreigners, colonization, and violent resource extraction, which scholar Edward Said associates with the virulent Orientalist ideology that accelerated European colonization in the 17th and 18th centuries, were in fact present in successful polities throughout the pre-modern world. Restricting our focus only to East Asia before 1900, the Mongols, Manchus, and Japanese all undertook violent colonial projects, ranging from the Korean Peninsula in the North, to Taiwan in the East, to Indochina in the South, to Xinjiang and Tibet in the West. Historical Orientalism was part-alibi, part-misidentification. On the one-hand, the professed physical and intellectual weakness or savagery of Eastern peoples was pure apologia for Western violence. On the other, real but emerging culture differences are, in hindsight, more correctly attributed to the waves of industrial revolution which reorganized European society. New machines of war, byproducts of the European Industrial Revolutions, made Orientalism more bloody than the colonial projects of antiquity.

Orientalism was further distinguished from earlier colonial ideologies by its professed claim to document and interpret foreign populations better than their own leaders. As the West in the 20th century began toying with the idea of international law--and as defeated imperial powers like the Qing and Ottomans recognized the need to introduce European industrial technology--this claim became a self-fulfilling prophecy, in a sense. The Western field of international political economy did gain more insight into these rapidly-Westernizing societies, surpassing those leaders who lost their authority or states; yet this insight largely came from the imposition of familiar Western constructs onto colonized populations. In late Qing China, the upper ranks of the customs bureaucracy became increasingly staffed by Britons[2] who governed the Chinese participating in the commercial system they themselves initiated. Yet ironically, the historical Orientalism combined with arrogance in the superiority of European systems was self-defeating. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 followed by the integration of several Warsaw Pact states into NATO, Francis Fukuyama heralded the "End of History." This was a phrase which happened to also mean the "End of Orientalism": once all societies were run like/by the West, all societies would think like the West, and if all societies thought like the West, all societies would be understood by the West. The universal, globalist order built on European norms symbolized the ultimate documentation, mastery, and civilization of the complex and heterogenous non-European world.

This would be all well and good if there was any absolute truth in the "civilization" of European institutions. The factory, the academy, the standing army, the nuclear family, the Church--if a golden mean of these faculties proved the universal law of human flourishing, Orientalism would truly be dead. For about a billion non-white people long-struggling to survive on a dollar a day, and millions of lives lost in violent conflict arising from arbitrary colonial borders and unsustainable securitization, and thousands of political activists arrested for "subversive" demands for better democracy than what's on offer in the liberal democracies, and a hundred world leaders fighting to preserve their national identity--and a few scrawny white boys from middle America--that death would be quite lamentable. Every patriotic American knows in their heart that our country has room to improve; every American has known the pain of a loved one struggling with drug addiction and felt the fear of being gunned down in school or on the streets. Yet the naysayers of Modern Orientalism tell us that there no improvements to be mode, that dialectic of history is optimized and uncontrollable, and that the individual's meaning in life is simply to conform to the times. It is not love for China that brought me here, for how can one love what one does not know? It was distaste for that complacency; it was the urge to liberate myself from objectivity.

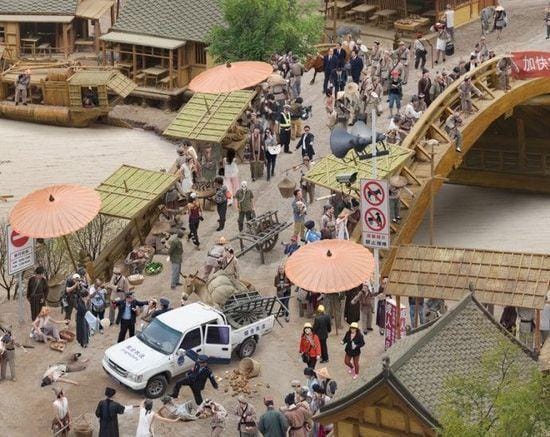

We know what we have learned, but we cannot know what is left to learn. As Master Zhuang says, "my life is bounded, but knowledge unbounded; to chase the unbounded using the bounded is ill-fated indeed."[3] This trip through China is a verification of that principle. To encounter the instincts, needs, and dreams of people in the most foreign of environments is to recognize what is subjective, truly a question of different value systems, and (like a Michelangelo sculpture) hack down into that which is universal: the shared human experience. It is my faith that the Chinese have found an alternative system to the West that runs by its own logic; rather than fighting against time or human instinct, society here exhibits a different aspect of humanity. In this series of "travelogues" I hope to introduce China though my sympathetic yet detached gaze. My goal is not to evaluate the Chinese system, but to faithfully depict it from as close a vantage point as a foreigner can possibly get. Thus: the bamboo pipe[4]. An ancient idiom for the work of an author (traditionally writing on bamboo slats), it describes the sliver of light one sees through a long gap; like looking through a periscope, through the aid of technology we see further, yet can only catch a glimpse of what we see. Finally, finishing this reflection a few months in to this journey, I can confirm I have not made a mistake in coming here. China is dangerously veering into conflict with the US-led system--and that prospect appeals to nobody.

- 人山人海

- https://review.gale.com/2017/08/17/robert-hart-and-the-chinese-maritime-customs-service/

- 《庄子》吾生也有涯,而知也无涯

- 管窥

Member discussion